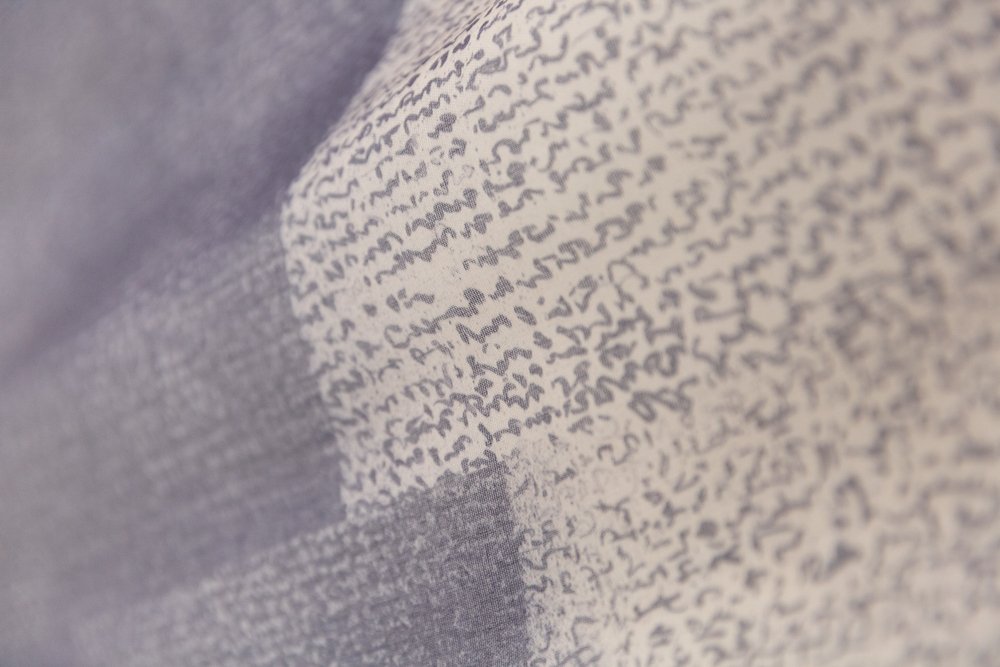

Hoard I (site responsive version), 2022. Dye sublimation print on IFR muslin, 228 x 560 cm

Hoard

project8/Cūrā8‘Digs’ is a slang term for describing home, and for this exhibition is understood as broadly encapsulating the shared human desire to materially inscribe place into space. Presented through the work of five local and international artists—Laura Cuch, Spencer Harrison, Jaime Powell, Tariku Shiferaw and Lisa Waup—this exhibition speculates upon the nature of material expression and spatial arrangement in the formation of personal places of habitation. As a curatorial proposition, DIGS considers some of the many ways that spaces are provisionally materially transformed into places using placeholders, architectural interventions, keepsakes and décor. Echoing our shared human desire to somehow create a sense of home, artists engage in the practice of creatively selecting, arranging and manipulating objects drawn from the continuum of lived experience to create experiences of place meaningfully delineated from everything else in the world. With this curious confluence in mind, the artists presented in DIGS variously explore the materiality of placemaking through printmaking, filmmaking, drawing, painting, animation, sculpture, and sculptural installation, and in doing so, reflect something of their unique cultural and social backgrounds. As anthropologist Michael Jackson put it in his 1995 book At Home in the World, the idea of home is lived as both a relationship and a tension. With this relational quality in mind, DIGS asks: How do we mark the places in which we sleep and eat? And in what kinds of ways do we ‘make do’ with that which is available to hand to construct a sense of home?

(Left): Hoard I (collage version), 2022, Digital collage, 25 x 30cm; Hoard I (site responsive version), 2022. Dye sublimation print on IFR muslin, 228 x 560 cm

Vivid in my memory of home: young men painting billboards high above the city, suspended with little more than jute rope. With the changing images, the billboards delivered a catalogue of time. Down on the ground, I observed this visual archive shift and accumulate: the city making and unmaking.

Amidst the lockdowns of 2020, the city of Hyderabad in the south of India cracked down on advertising hoardings ostensibly for safety and aesthetic reasons. The rules on dimensions and proportions were tightened so much, it effectively banned that feature of many an Indian skyline. The measures were taken following the removal of 300 disused steel frames across the city two years prior. The towering, rusting skeletons were left to the elements until the only course was their complete destruction, and the denial of the right of others to exist even if in excellent condition.

Billboards are one object of shared culture. What happens when the situation is more challenging than this? What else is lost when we disregard and neglect what’s left behind? If we do not care for what is shared, how can we care for each other? How do the remnants of history act as signifiers of our present responsibilities? In its simplest form, History is a sequence of reasons for how we have gotten here. In the Indian context, this simple version of ‘doing’ history is Itivrtta, the events and facts. However, the more common translation – Itihasa – speaks to History as a dialogue between the present and the past. Itihasa is concerned with meaning, debate, memory and order in society. It is malleable, focused on the everyday. When memories are long, Itihasa becomes a collective historical consciousness.

Since the 1500s, Hyderabad was ruled by the impossibly wealthy and defiantly independent Qutub Shahs and the Nizams. The state was brought kicking and screaming into the Dominion of India by military action in 1948. Today, the architecture of Indo-Islamic and Indo-Saracenic styles that flourished are in desperate condition. Palaces, hospitals, Mosques and many other public and privately owned structures are left to disintegrate under the intense drought alternating with powerful monsoons. With no political will to upkeep, demolition is eventual. Buildings mysteriously disappear from heritage registers. In 2020 alone Saifabad Palace and Asman Garh Palace, both built in the 1880s, were demolished. Until then, these ghosts of Itihasa lurk in the city.

The bones of the city take up so much of my imaginings of home, maybe because of its precise state; less splendid than acceptable, but not yet ruins. Its existence is a perpetual anguished yearning. I've struggled with ownership over my Indianness, the language, art and food. But Hyderabad, meri jaan, I keep your debris in my heart. My billboard might never exist in the physical world, save the imagined photograph. It sits with the watchful jinn as a net, capturing and reflecting collective stories, upholding Itihasa.

Images by Lucy Foster

Exhibition view including Lisa Waup, TSOL, 2021, and LOST, 2021